RECAP Featured in XRDS Magazine

XRDS Magazine recently ran an article by Steve Schultze and Harlan Yu entitled Using Software to Liberate U.S. Case Law. The article describes the motivation behind RECAP, and outlines the state of public access to electronic court records.

Using PACER is the only way for citizens to obtain electronic records from the Courts. Ideally, the Courts would publish all of their records online, in bulk, in order to allow any private party to index and re-host all of the documents, or to build new innovative services on top of the data. But while this would be relatively cheap for the Courts to do, they haven't done so, instead choosing to limit "open" access.

[...]

Since the first release, RECAP has gained thousands of users, and the central repository contains more than 2.3 million documents across 400,000 federal cases. If you were to purchase these documents from scratch from PACER, it would cost you nearly $1.5 million. And while our collection still pales in comparison to the 500 million documents purportedly in the PACER system, it contains many of the most-frequently accessed documents the public is searching for.

[...]

As with many issues, it all comes down to money. In the E-Government Act of 2002, Congress authorized the Courts to prescribe reasonable fees for PACER access, but "only to the extent necessary" to provide the service. They sought to approve a fee structure "in which this information is freely available to the greatest extent possible".

However, the Courts' current fee structure collects significantly more funds from users than the actual cost of running the PACER system.

Using Software to Liberate U.S. Case Law By Harlan Yu and Stephen Schultze

"Ignorance of the law is no excuse." This legal principle puts the responsibility on us—the citizens—to know what the law says in order to abide by it. This principle assumes that citizens will have open access to the laws that our government prescribes so that we will have adequate opportunity to learn our civic obligations. A complimentary legal principle obligates the justice system to provide equal access to the law for all citizens, without regard to social or economic status.

While these may seem like basic conditions in a democracy, equal and open access to the law in the United States (U.S.) has been a work-in-progress. In past generations, access meant not only equal rights to petition the court and defend yourself, but also the ability to sit and observe the government from the gallery of a legislative chamber or a courtroom. It also meant obtaining copies of written records that document these activities. Of course, for those who didn’t have the time or money to physically visit the courthouse or buy expensive compendiums of decisions, the law often remained opaque and unknown. These limitations to access were consequences of the analog format, which made obtaining vast amounts of information neither easy nor cheap.

But as society embraces digital distribution of information over the Internet, the potential for equal and open access to the law is no longer limited by physical constraints. Digital distribution is instantaneous, cheap, and will eventually reach all corners of our society.

The U.S. Courts were among the first in the government to recognize this enormous potential. They began building a system in the early 1990s called PACER—Public Access to Court Electronic Records—that started out as a dial-up system and eventually transitioned to a graphical Web interface. The system provides access to all of the raw documents in federal court proceedings since its inception. But while PACER has without a doubt expanded public access to federal court information, the government has yet to harness digital technologies in a way that realizes the full potential for equal and open access that they present.

How PACER Limits Access

PACER makes hundreds of millions of court documents available online to the public. Using the system to find relevant information, however, can be quite a challenge.

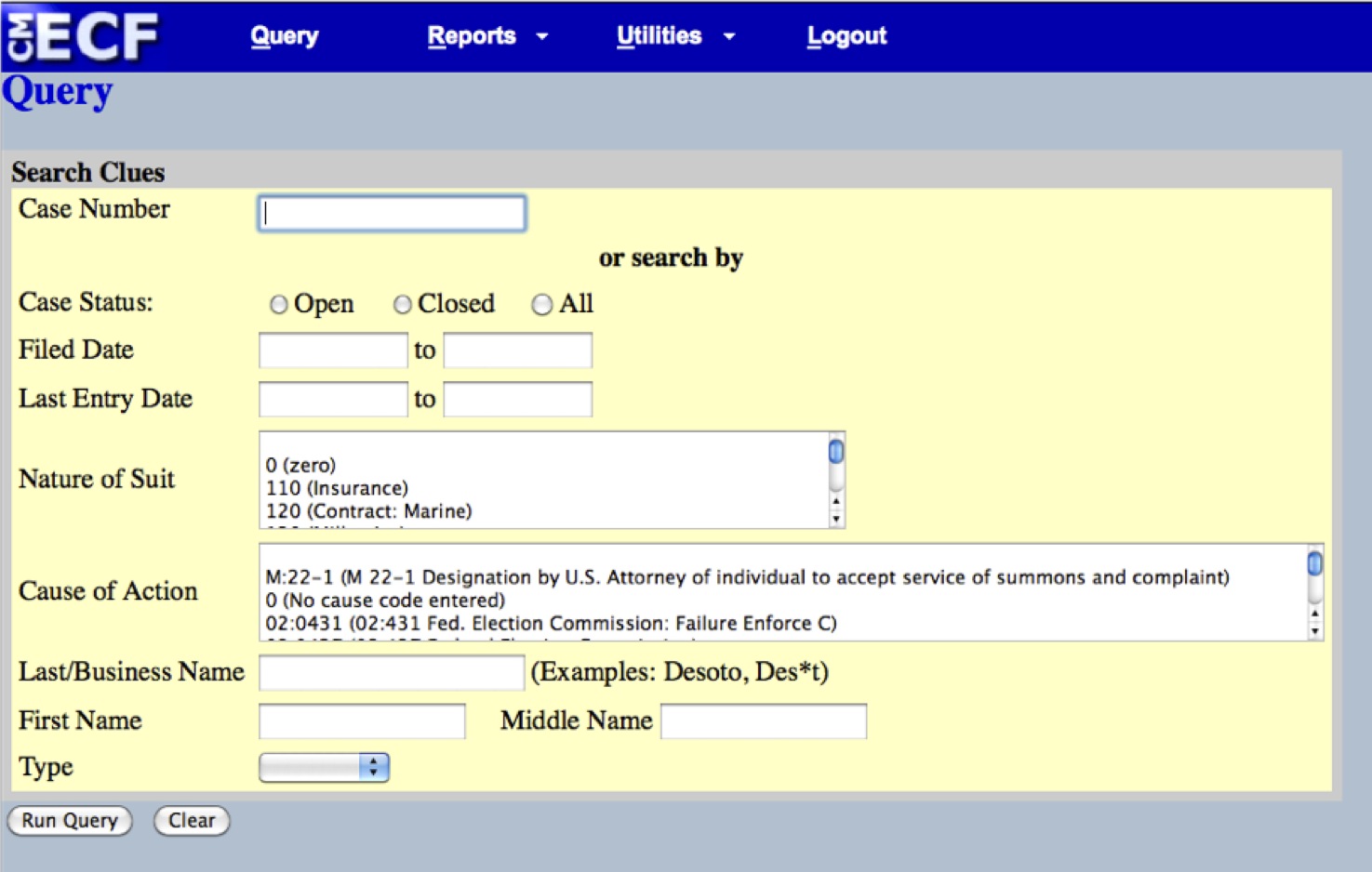

The entire PACER system is made up of about 200 individual data silos—one instance of the PACER software for each of the federal district, bankruptcy, and circuit courts—and the system provides very limited functionality to search across all of the silos. Within each silo, it’s only possible to do a search over a few fields, rather than over the full-text of all of the available documents—a stark contrast to what’s possible on modern Web search engines. Indeed, because of PACER’s walled-garden approach, search engines are unable to crawl its contents. The interface also relies heavily on legal jargon, making it difficult for citizens to figure our where and how to search (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The PACER search interface for the Southern District of New York.

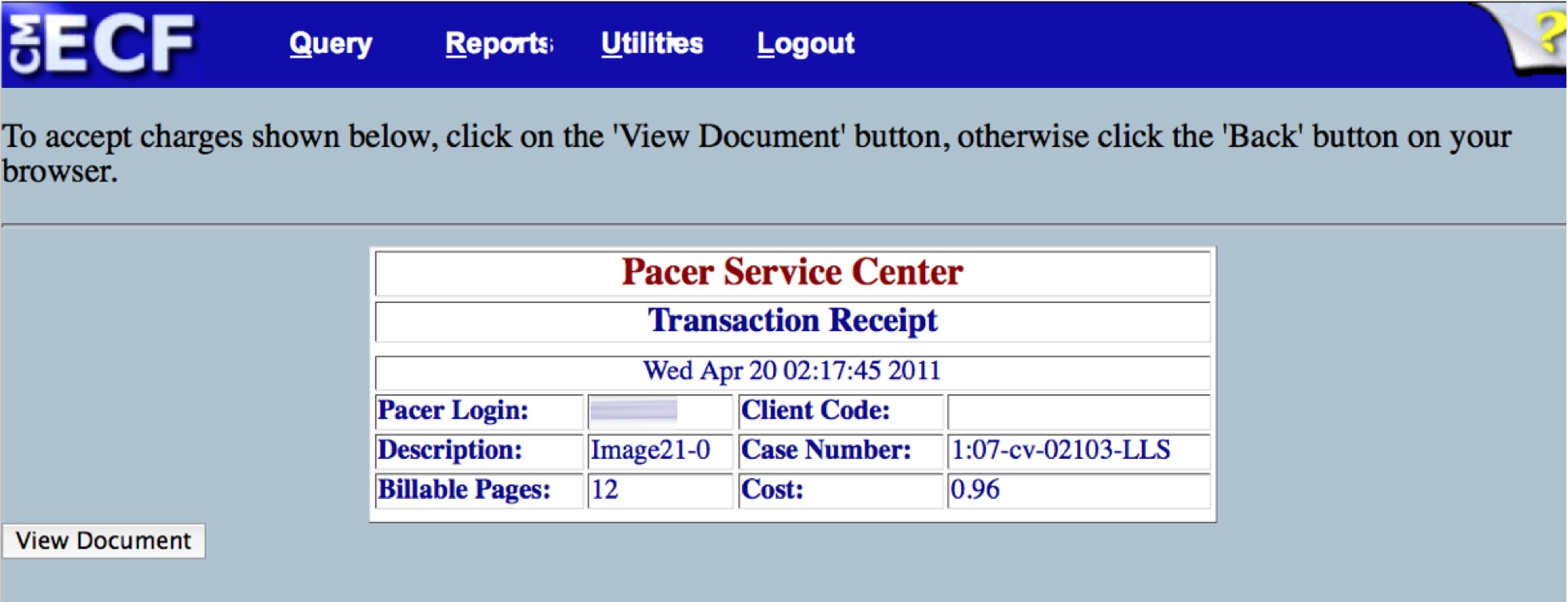

But the biggest problem with PACER by far is its pay-for-access model. The Courts charge PACER users a fee of eight cents per page to access its records (see Figure 2). This means that, when looking for documents, searches will cost eight cents for every 4320 bytes of results—one “page” of information according to PACER’s policy. Getting a docket that lists all the documents in a case can cost the user a couple of dollars. To download a specific document, say a 30-page PDF brief, the user would be charged another $2.40 for the privilege. While each individual charge may seem small, the cost incurred by using PACER for any substantial purpose racks up very quickly. Repeated searching using the limited interface can become particularly costly.

Figure 2. PACER receipt page for purchasing a court document.

Even at many of our nation’s top law schools, access to the primary legal documents in PACER is limited for fear that their libraries’ PACER bills will spiral out of control 1. Academics who want to study large quantities of court documents are effectively shut out. Also affected are journalists, non-profit groups, and other interested citizens, whose limited budgets make paying for PACER access an unfair burden. From the Court’s own statistics, nearly half of all PACER users are attorneys who practice in the federal courts, which indicate that PACER is not adequately serving the general public 2. The pay-for-access model bears much of the blame.

Furthermore, the Courts do not provide any consistent machine-readable way to index or track cases, even though all of this information is gathered electronically and stored in relational databases. Anyone seeking to comprehensively analyze case materials faces an uphill battle of reconstructing the original record.

Using PACER is the only way for citizens to obtain electronic records from the Courts. Ideally, the Courts would publish all of their records online, in bulk, in order to allow any private party to index and re-host all of the documents, or to build new innovative services on top of the data. But while this would be relatively cheap for the Courts to do, they haven’t done so. The reason will be explained in a later section.

Liberating Court Records with RECAP

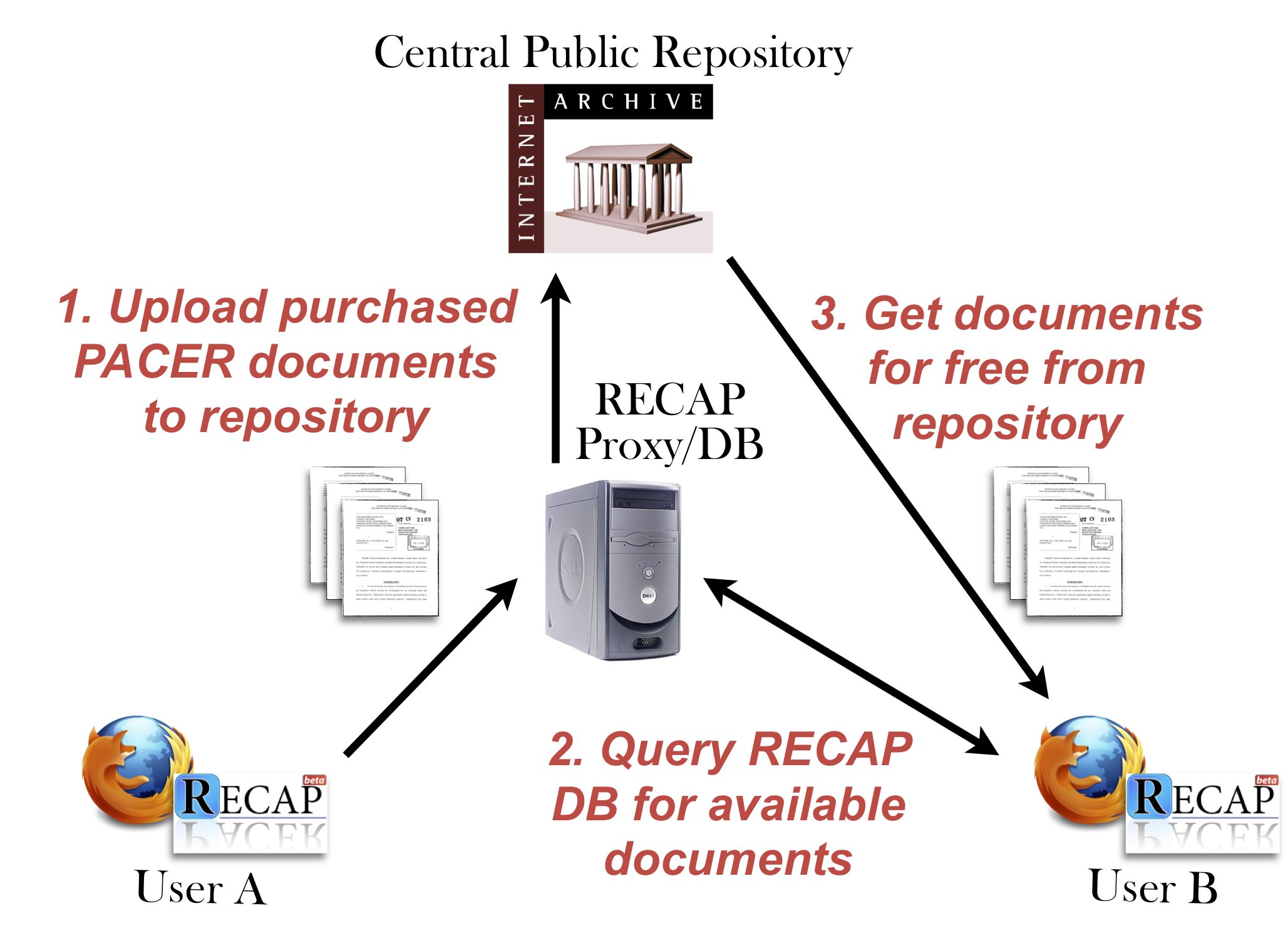

Because everything in PACER is part of the public record, users can legally share their document purchases freely once they have been legitimately acquired. Recognizing this possibility, we created a Firefox extension called RECAP—to “turn PACER around” 3. RECAP crowdsources the purchase of the PACER repository by helping users to automatically share their purchases. The extension provides two primary functions (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Diagram of the RECAP document sharing model.

First, whenever a user purchases a document from PACER, the extension will automatically in the background upload a copy of the document to our central repository hosted by the Internet Archive, where it will be indexed and saved. This effectively liberates that document from behind the PACER paywall.

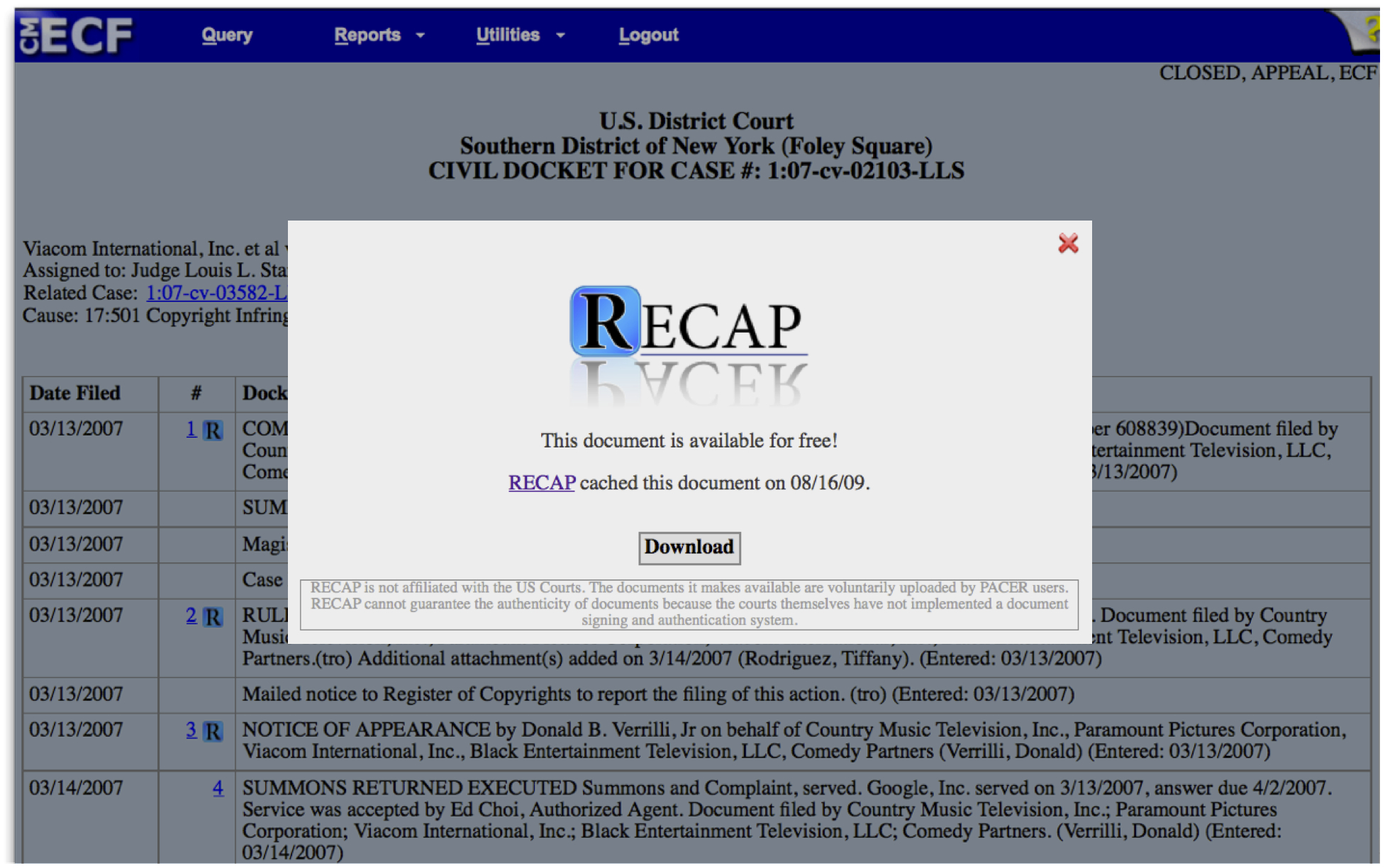

Second, RECAP helps PACER users save money by notifying them whenever documents are available from the shared central repository. Whenever a user pulls up a docket listing, the extension will query the central RECAP database to check whether any of the listed documents are already in our repository. If so, the extension will inject a small RECAP link next to the PACER link to indicate that the user can download the document for free from our repository, rather than buying it again from PACER (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Accessing documents from RECAP while using PACER.

When RECAP was released in August 2009, the Courts reacted somewhat impulsively. They issued warnings to PACER users that RECAP might be dangerous to use because it was “open source” software, but ultimately they had no legal recourse against a tool that simply helped citizens to exercise their right to share public records.

Since the first release, RECAP has gained thousands of users, and the central repository contains more than 2.3 million documents across 400,000 federal cases. If you were to purchase these documents from scratch from PACER, it would cost you nearly $1.5 million. And while our collection still pales in comparison to the 500 million documents purportedly in the PACER system, it contains many of the most-frequently accessed documents that the public is searching for.

Why the Courts Resist Open Access

With PACER’s many limitations, it’s not difficult to imagine how one might build a better, more intuitive online interface for access to court records. Indeed, a group of Princeton undergraduates spent a semester building a beautiful front-end on top of our repository, called the RECAP Archive, available at archive.recapthelaw.org. Access to case law would be much improved if all of PACER’s records were available within the RECAP Archive. But it’s unlikely that the Courts will voluntarily drop the PACER paywall any time soon.

(Update, 2016-11-04: archive.recapthelaw.org has been replaced with a new version here.)

As with many issues, it all comes down to the money. In the E-Government Act of 2002, Congress authorized the Courts to prescribe reasonable fees for PACER access, but “only to the extent necessary” to provide the service. They sought to approve a fee structure “in which this information is freely available to the greatest extent possible” 4.

However, the Courts’ current fee structure collects significantly more funds from users than the actual cost of running the PACER system. We examined the Courts’ budget documents from the past few years, and we discovered that the Courts claim PACER expenses of roughly $25 million per year. But in 2010, PACER users paid about $90 million in fees to access the system 5. The extra funds are deposited into a fund for IT projects for the Courts. This fund is used to purchase a diversity of unrelated things for the Courts, like flat screen monitors in courtrooms and state-of-the-art AV systems. While we support the Courts’ adoption of these modern technologies, it shouldn’t come at the direct expense of legally mandated open access to court records.

Indeed, the reported figure of $25 million per year to run PACER either wildly over-estimates the actual cost, or is a reflection of a system that’s built horribly inefficiently, perhaps both. The cost of making a few hundred terabytes of data available on the Web is not low, but in an era of abundant and ever-cheaper cloud storage and hosting services, it also shouldn’t be anywhere near the claimed costs. The Courts’ highly distributed infrastructure—each courthouse manages its own servers and private network links—may have made sense two decades ago, but today it only perpetuates higher than necessary costs and barriers to citizen access.

The Decline of Practical Obscurity

One significant challenge in opening up federal court records is the concern over personal privacy. Many of life’s dramas play themselves out in our public courtrooms. Consider in cases concerning divorce, domestic abuse and bankruptcy. Many intimate private details are revealed in these proceedings and are part of public case records.

Before electronic records, the Courts relied on the notion of “practical obscurity” to protect sensitive information. That is, because these documents were only available by physically traveling to the courthouse to obtain the paper copy, the sensitive data contained therein—while public—were in practice obscure enough that very few people, if anyone, would ever see them.

Only in 2007 did the Courts define formal procedural rules that required attorneys to redact certain sensitive information from court filings. But not only were the Courts not very diligent at enforcing their own rule, older documents which were subsequently scanned and made available electronically contain substantial amounts of sensitive information, such as Social Security numbers and names of minor children.

A preliminary audit conducted by Carl Malamud found that more than 1,500 documents in PACER, out of a sample of 2.7 million documents, contain unredacted social security numbers and other sensitive information 6. Research by Timothy Lee, our fellow RECAP co-creator and computer science student at Princeton, studied the rate of “failed redactions” in PACER, where authors simply drew a black box over the sensitive information in the PDF, leaving the sensitive information in the underlying file. He estimated that tens of thousands of files with failed redactions exist in PACER today 7.

PACER’s paywall attempts to extend practical obscurity, at least temporarily, to the digital realm, since it prevents the documents behind it from being indexed by major search engines. But over time, these documents will ultimately make their way into wider distribution, whether through RECAP or other means. Large data brokers already regularly mine PACER for personal data. The resulting decline in practical obscurity will ultimately force the Courts to deal more directly with the privacy problem.

This may mean that documents will need to be more heavily redacted before they are filed publicly, or in some cases, entire documents will need to be sealed from public view. It is not always easy to align privacy and open access, but what’s clear is that the Courts ought to make more explicit determinations about which data are sensitive and which are not, rather than relying simply on the hope that certain records won’t often be accessed.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, more openness can help lead to more privacy if citizens become aware of what information is contained in public records and more proactively choose what to include and when to petition for redaction or sealing. A more accessible corpus also provides opportunities for researchers to devise new methods to protect personal privacy while enhancing the accessibility of the law.

The Courts can benefit from improved technology and smart computer scientists in this task. In our initial research in this area, we already identified several ways for the Courts to more automatically identify and redact sensitive information. Using text analysis and machine learning techniques, and what we already know about the prevalence of sensitive information in the PACER corpus, we can try to prioritize documents for human review, starting with the documents that are most likely to contain sensitive information.

Conclusion

The PACER paywall is a significant barrier to public participation in the U.S. justice system. Online access to court records, through innovative third-party services, has the potential to serve as the spectators’ gallery of the 21st century. But without free and open access to the underlying data, it is nearly impossible for developers to build new, useful services for citizens.

Digital technologies present our Courts with a key opportunity to advance our Founders’ vision of forming a more perfect Union, with equal justice under the law. Opening up free access to all electronic court records would mark a significant step in our collective journey.

Biographies

Harlan Yu is a Ph.D. candidate in Computer Science at Princeton University, affiliated with the Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP). His primary research interests include computer security, privacy and open government. He received his BS from UC Berkeley and his MA from Princeton.

Stephen Schultze is the Associate Director of the Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton University. His work at CITP includes internet privacy, computer security, government transparency, and telecommunications policy. He holds degrees from Calvin College and MIT.

Disclaimer

© ACM, 2011. This is the author’s version of the work. It is posted here by permission of ACM for your personal use. Not for redistribution. The definitive version was published in ACM XRDS, Vol. 18, Issue 2, Winter 2011. http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2043236.2043244

Footnotes

-

Erika V. Wayne, PACER Spending Survey, on the Legal Research Plus blog, August 28, 2009. http://legalresearchplus.com/2009/08/28/pacer-spending-survey/ ↩

-

Harlan Yu, Assessing PACER’s Access Barriers, on the Freedom to Tinker blog, August 17, 2010. https://freedom-to-tinker.com/blog/harlanyu/assessing-pacers-access-barriers ↩

-

RECAP: Turning PACER Around. https://free.law/recap/ ↩

-

U.S. Senate Report 107-174, 107th Congress, 2nd Session, p. 23, ↩

-

Stephen Schultze, What Does it Cost to Provide Electronic Public Access to Court Records?, on the Managing Miracles blog, May 29, 2010. http://managingmiracles.blogspot.com/2010/05/what-is-electronic-public-access-to.html ↩

-

Carl Malamud, Letter to the Honorable Lee H. Rosenthal, October 24, 2008. https://public.resource.org/scribd/7512583.pdf ↩

-

Timothy B. Lee, Studying the Frequency of Redaction Failures in PACER, on the Freedom to Tinker blog, May 25, 2011. https://freedom-to-tinker.com/blog/tblee/studying-frequency-redaction-failures-pacer ↩